Death is the final arbiter after all and the Bible offers the only hope for mankind, since not only is the book historically accurate but, also, no other writings have been attributed to having been inspired by the Lord God who wrote the Ten Commandments with His own Finger.

Archaeological discoveries in recent times have vindicated numerous details in the Bible.

The following are summaries of arguments that I have made in depth (along with many more), with scientific documentation, in my book, The Word Set in Stone: How Archaeology, Science, and History Back up the Bible (Catholic Answers Press, March 15, 2023).

1. Skeptics have asserted for many years that Jesus’ hometown of Nazareth (Luke 4:16) did not exist at all in his time. But alas, in 2009 British-Israeli archaeologist Yardenna Alexandre announced the first archaeological proof of a home in Nazareth dating from the lifetime of Jesus.

2. The existence and office of Pontius Pilate have been verified in mentions by ancient historians Josephus, Philo and Tacitus — and, notably (as the first physical proof), in the “Pilate Stone,” found in 1961 at Caesarea Maritima, on the Mediterranean coast of Israel. It contained his entire name (see Luke 3:1; Acts 4:27; 1 Timothy 6:13).

3. Capernaum, Peter’s hometown (Luke 10:15) has long since been excavated. But in 1968, a very old church was found, built over a house believed to be that of St. Peter. Moreover, in 1981, beneath the beautiful white limestone synagogue, a black basalt building dating from the first century was discovered: the synagogue where Jesus preached (Luke 4:31-36).

4. Until 1968, no physical evidence of crucifixion had ever been found. Thus, many held that victims were attached to crosses with ropes. But in that year, Greek-Israeli archaeologist Vassilios Tzaferis found in Jerusalem a man who had been crucified in the first century. The remains included a heel bone with a nail driven through it from the side.

5. Luke’s precision extends to particular titles of rulers. For example, King Agrippa I is accurately titled “king” (Acts 12:1) rather than “tetrarch” — like other seemingly similar rulers (see Matthew 14:1; Luke 3:1, 19, 9:7; Acts 13:1) — and history records that he was the last ruler with the title of “king” who reigned over Judea.

6. How about a more “dramatic” and seemingly “fantastic” alleged event, such as Herod (Agrippa) being “eaten by worms” (Acts 12:21–23)? Ascariasis is a condition in which roundworms can become parasites in human intestines, sometimes causing death. Other known medical conditions also entail worms or similar creatures infesting the human body — such as myiasis, which involves fly larvae (maggots).

7. Acts 13 mentions Paul and his companions sailing to the island of Cyprus and meeting Sergius Paulus, a “proconsul” (13:4, 7). Cyprus became a “senatorial province” in 22 B.C. and hence was governed by a proconsul. An inscription mentioning “proconsul Paulus” was discovered at Soloi, Cyprus, in 1878.

8. Philippi, mentioned in Acts 16:12 (see also 20:6), was “the leading city of the district of Macedonia,” according to Luke. But scholars fretted over his use of the Greek word meris (“district” in RSV), which was thought to be highly improbable and inaccurate. Excavations in Fayum in Egypt showed that colonists in that town who immigrated from Macedonia, used this very word meris to denote the divisions of a district.

9. Luke refers to “Lydia, from the city of Thyatira, a seller of purple goods” (Acts 16:14). As a result of inscriptions, we now know that Thyatira had many trade guilds, and one that was dominant was the production of purple dye. Indeed, 15 of 28 inscriptions found in Thyatira regarding dye were related to this trade of purple dye.

10. Luke’s attention to meticulous detail was so comprehensive that it extended even to particular terms of disdain used by Stoic philosophers in Athens, who insulted Paul when he preached to them. The Greek noun spermologos — literally “seed-picker” (“babbler” in Acts 17:18, RSV) — was usually used to describe a type of finch. Luke, in his use of this Greek word (only here in the New Testament), exhibits an extraordinary awareness of Athenian Stoic culture and slang, since this was a word used by Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, to insult one of his followers (see Diog. Laert. Zeno, c. 19).

11. Luke’s knowledge extends to fine points of Roman law as well. Luke records Paul saying to a Roman centurion, “Is it lawful for you to scourge a man who is a Roman citizen, and uncondemned?” (Acts 22:25). Here, Paul was appealing to what is known as the Porcian laws, particularly Lex Porcia II (Lex de Porcia de tergo civium). It extended the right to provocatio (appeal to the plebeian tribune) against flogging.

12. Luke mentions that prisoner Paul “was allowed to stay by himself” (Acts 28:16) and lived “two whole years at his own expense” (28:30). This accurately reflects the widespread Roman practice of keeping less dangerous criminals under house arrest.

13. The location of Jacob’s Well is in Sychar (John 4:5-6). John 4:6 (twice) and 4:14 use the Greek word pégé, which means “spring” or “fountain” (compare 2 Peter 2:17; James 3:11). On the other hand, in 4:11–12, a different Greek word is used: phrear, which means “well” or “cistern” (see Luke 14:5). This perfectly describes Jacob’s Well, which is both a dug-out well and running spring, cut through soft limestone rock. Its water comes from underground sources, making it a true well, and by percolated surface water, which makes it a cistern.

14. The Pool of Siloam (John 9:7) was rediscovered during work on a sewer in the autumn of 2004. Archaeologists Eli Shukron and Ronny Reich uncovered some stone steps, and it quickly became evident that they were likely part of the Second Temple-period (516 B.C.–A.D. 70) pool.

15. Caiaphas was Annas’ son-in-law, as John 18:13 notes, and as we know from Josephus, and he was the high priest (John 18:13) from the years A.D. 18 to 36, Annas had been high priest from A.D. 6 to 15. Mosaic Law (Numbers 35:25, 28) implies that high priests were still called by that title even after leaving office. This easily explains Luke 3:2 (“in the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas”). Matthew calls Caiaphas “high priest” twice (26:3, 57).

JERICHO:

DOES

THE EVIDENCE DISPROVE OR PROVE THE BIBLE?

Author: Jerold

Aust

Category: Conquest Of Canaan Under Joshua

& The Inception Of The Period Of The Judges 1406-1371 BC

Created:

30 January 2009

Kathleen Kenyon declared the biblical story to be false and the academic world accepted her conclusions. Do her conclusions hold up to scrutiny?

This article was first published by ABR in the spring 2003 issue of Bible and Spade.

The ancient city of Jericho lay about 6 mi (10 km) from the Jordan River and about 7.5 mi (12 km) northwest of the dead sea, 670 ft (204 m) below sea level and about 3,000 ft (914 m) below Jerusalem, 14 mi (22 km) away. A large gushing spring and the fertile plain surrounding the city earned it the distinction 'the city of palm trees' (Dt 34:3; 2 Chr 28:15). A major east-west road ran next to the city, intersecting with the Jordan at a ford nearby, making Jericho a strategic crossroads.

The city had already been occupied for many centuries before the Israelites arrived. It had an inner wall and an outer fortified wall, several feet thick, enclosing about 9 acres of land. To the Israelites entering the Promised Land, Jericho presented a major obstacle.

According to the bible, Joshua and the Israelites crossed the Jordan in the springtime and then celebrated the Passover on the plains outside Jericho, eating some of the fresh grain of the land since it was harvest time (Jos 3:15-17; 5:10-12). For seven days the Israelites marched around the city, accompanied by priests blowing trumpets. On the seventh day, after their seventh circuit around the city, the priests blew their trumpets, the people shouted, and the walls of the city, as the old song goes, 'came a-tumblin' down.'

Then the people went up into the city, every man straight before him, and they took the city. And they utterly destroyed all that was in the city...with the edge of the sword' (Joshua 6:20-21, NKJV).

Section drawing of the north balk of Kathleen Kenyon’s 1950s west trench through the fortification system at Jericho. The yellow area is what remains of the earthen embankment that surrounded the tell at the time of the conquest. It was held in place by a stone retaining wall. Atop the retaining wall and also at the crest of the embankment there were once mud brick walls. When the walls collapsed (Jos 6:20), they were deposited at the base of the retaining wall, shown.

Only Rahab, who had hidden the Israelite spies, and her family were spared from the destruction (Jos 6:17, 22-26). The Israelites burned the city and all that was in it (vs 24). Over later centuries other peoples occupied, built on and abandoned the same site many times. Eventually it grew into a huge mound of earth and rubble several dozen feet high.

In the 19th and 20th centuries several organized excavations were carried out at the site. The most notable were those of the British archaeologists John Garstang (1930-1936) and Kathleen Kenyon (1952-1958). Garstang found fallen city walls, burned stores of grain and evidence of destruction of the city by fire, all of which he dated to about 1400 bc-right in line with the biblical chronology of the city's destruction.

Kathleen Kenyon found much of the same evidence-collapsed walls, stores of grain and an ash layer from a massive conflagration. However, she reached a completely different conclusion. Rather than supporting the biblical account, her finds at Jericho, she said, disproved the biblical story. Why? She dated the city's destruction to around 1550 BC, meaning the site had been abandoned and therefore there was no city for the Israelites to capture at the time of the conquest.

Jericho retaining wall from the time of the conquest that held in place an earthen embankment, Italian-Palestinian excavation, 1997. The Israelites marched around this wall for seven days. When the mud brick city walls collapsed, they were deposited at the base of the retaining wall forming a ramp by which the Israelites could enter the city (see drawing).

Her statements had a major impact on the

scholarly world. Many hailed her findings as proof that the bible was

historically unreliable, that it couldn't be trusted. The only logical

conclusion, agreed the scholars, was that its supposed historical annals were

but myth fabricated much later in Israel's history. This became the accepted

reality, entrenched in archaeological and academic circles.

Kathleen Kenyon died in 1978. However, detailed reports on her findings at Jericho weren't published until 1981-1983. Several years later, when archaeologist Bryant Wood—

then a visiting professor at the university of Toronto—examined her findings, he was surprised to find that 'Kenyon’s analysis was based on what was not found at Jericho rather than what was found' (1990:50).

He realized she had based her dating on the fact that she did not find a particular kind of imported pottery found at other sites in the near east-thus Jericho must have been unoccupied at the time. The problem, Dr. Wood learned, was that she had excavated in a poor section of town in which the inhabitants could not have afforded to buy and use such imported pottery.

More surprising still, he discovered that Kathleen Kenyon actually had found indigenous pottery that dates precisely to the time of the biblical conquest of the city, but inexplicably ignored it. She also overlooked the fact that her predecessor, John Garstang, had found painted pottery from the time of the conquest. Egyptian amulets he found at a nearby cemetery also indicated the site was regularly inhabited from several centuries before until right around the biblically derived date of the city's fall. Thus there was no occupation gap as she had supposed.

In spite of such major problems with her conclusions, Kenyon’s view remains entrenched in the minds of many to this day. Yet in reality what Kenyon, Garstang and other excavators have found at Jericho correlates precisely with the account in the book of Joshua. They found collapsed walls, not walls that were broken down from the outside but that had fallen down (Jos 6:20). The walls had not fallen inward, but outward, creating a ramp of fallen bricks by which the Israelites 'went up into the city, every man straight before him' (Jos 6:20).

The unusually large stores of carbonized

grain found in the ruins showed that the city had endured only a short siege,

which the bible numbers at seven days (jos 6:12-20), and that the grain had

been recently harvested (Jos 3:15). Also, because grain was a valuable

commodity almost always plundered by conquering forces, the large amount of

grain left in the ruins is puzzling-but consistent with god's command that

nothing in the city be taken except valuable metals to be used for the treasury

of the lord (Jos 6:24).

The city had also been burned, exactly as the bible records (Jos 6:24). As Kathleen Kenyon herself noted:

The destruction was complete. Walls and

floors were blackened or reddened by fire, and every room was filled with fallen

bricks, timbers, and household utensils; in most rooms the fallen debris was

heavily burnt, but the collapse of the walls of the eastern rooms seems to have

taken place before they were affected by the fire (wood 1990:56).

As she observed, the walls had collapsed

before the city was burned-again, exactly as the bible states.

Abraham was the first and greatest of the Hebrew patriarchs; his story unfolds over 15 chapters in the book of Genesis (from Gen. 11:26-Gen. 25:8). The Lord called him out of his own country to a new land and promised to bless the earth through him (Gen. 12:1-3).

In our next top ten list, we’ll look at the top ten discoveries in biblical archaeology related to Abraham. Archaeological evidence is almost always fragmentary and incomplete, especially the father back in time one looks. That said, there are numerous finds which demonstrate that the patriarchal narratives of Scripture accurately reflect the time period in which they are set.

According to conventional chronology which interprets the biblical data (1 Kings 6:1; Ex. 12:40-41; Gen. 47:9; Gen. 25:26; Gen. 21:5) in a straightforward way, Abraham (then known as Abram) was born ca. 2166 BC.1 If this is correct, Abraham was born in the Intermediate Bronze Age, but lived most of his life in the Middle Bronze Age, which began ca. 2100 BC.2 Other Bible scholars interpret the numerical date in an honorific way, rather than as literal base-10 numbers, and believe Abraham lived later in the Middle Bronze II period (ca. 1900-1550).3

Here, for the most part, I’ve chosen items that would be generally agreed upon by both groups of scholars, regardless of their chronology. Thus, I have not included finds like Tall el-Hammam4, whose identity is heavily dependent on one’s chronology (some believe it is biblical Sodom, others do not).

Here then are the top ten sites and finds in biblical archaeology that related to Abraham.

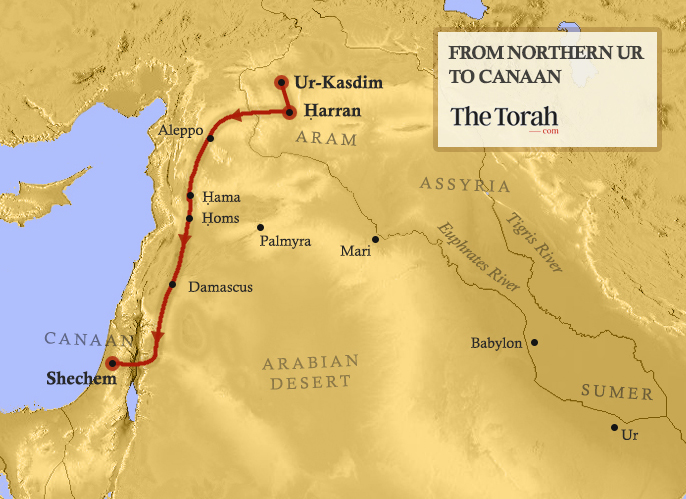

10. City of Ur

Two ancient cities are the primary candidates for Ur of the Chaldeans (Hebrew: Kasdim): Urfa in modern-day Turkey, the center of the Hurrian civilization, and Tell el-Muqayyar in modern-day Iraq, the Sumerian city of Ur. According to Mark Wilson, “The consensus of an earlier generation was that the Anatolian Ur was Abraham’s Ur. When Leonard Woolley discovered the royal cemeteries at Sumerian Ur in 1927, he declared that his finds were ‘worthy of Abraham.’”5 Ever since, the consensus has been that the Sumerian Ur was Abraham’s birthplace.6 There are convincing reasons to believe the earlier generation may have correctly identified the Anatolian Ur as Abraham’s hometown. Old Testament professor, Tony W. Cartledge, notes, “Some ancient sources, however, suggest that the Chaldeans’ original home was in Anatolia, now a part of Turkey, before some of them migrated south [to Mesopotamia].”7 Moreover, when Abraham sends his servant to choose a wife for his son Isaac, he directs him to “go to my country and to my own relatives” (Gen. 24:10). His servant went to the city of Haran in Aram-Naharayim (“Beyond the River”), a region east of the Euphrates River, which fits the description of the northern Ur, but not the southern one. The ancient city of Haran in modern-day Turkey is 24 miles/44km southeast of Urfa, and it make sense that Abraham’s servant would go here, the region of Abraham’s birth, to find a wife for his master’s son. Unfortunately, today a city of 2 million people covers the site of ancient Ur.

9. City of Haran

After Abraham left Ur, he settled in Haran for years, before making his way to Canaan (Gen 11:31; Acts 7:2-4). Tell Haran is located on the fertile plain of the Balikh River, a major tributary of the Euphrates River. In ancient times it lay at the junction of major trade routes. It was a major center for the worship of the moon-god Sin. Excavations have unearthed a large mudbrick building that dates to the end of the third millennium BC, which some believe may have been a predecessor to the Temple of Sin.8 Abraham’s father, Terah, may have worshiped the god Sin here, as Scripture records, “your fathers lived beyond the Euphrates, Terah, the father of Abraham and of Nahor; and they served other gods” (Josh. 24:2). Haran is famous for its conical beehive houses, a style that has been used in Mesopotamia for thousands of years; the ones seen today at Haran were only built in the last 200 years.9

8. Gate at Tel Dan

The famous Middle Bronze Age arched gate at Tel Dan has often been called, “Abraham’s gate” because Abram once rescued his nephew, Lot, from his kidnappers near the city (Gen. 14:14). The imposing mudbrick gate was constructed in the 18th century BC by the Canaanites at Lesham (Dan) on the eastern side of the city. It survives today at a height of 47 courses, and at one time featured three enormous arches which framed the entrance to the city.10 A staircase led up to the gate from the surrounding plain and traces of the white plaster that originally covered the doorway can still be detected. Mysteriously, it was only used for about 50 years before it was covered over by an earthen rampart, which preserved it.11 The gateway at Tel Dan was likely constructed a couple of centuries after Abraham’s death; it is included in this list because of its association with him and because it is an example of the gate systems that would have been familiar to the patriarchs.

7. The Battle of Siddim

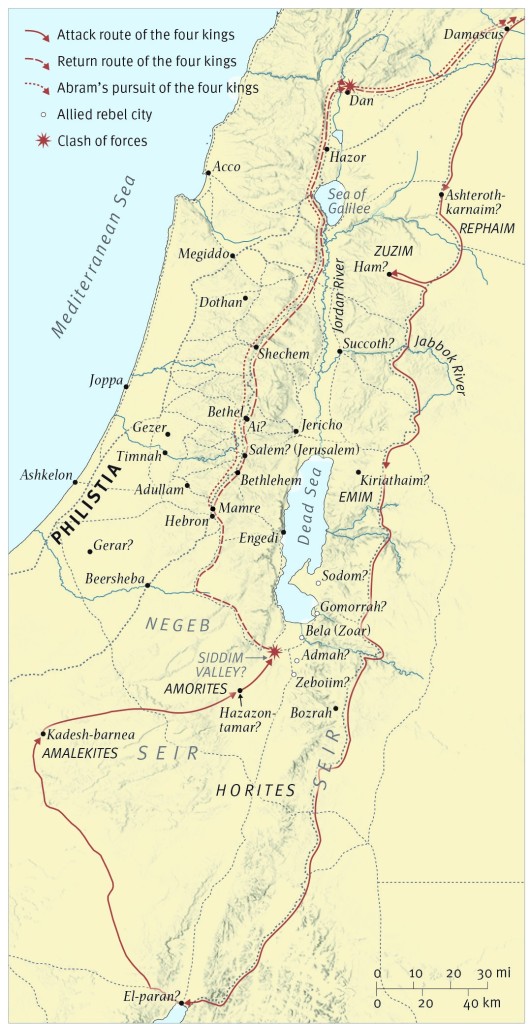

Genesis 14:1-3 records the Battle of Siddom: “In the days of Amraphel king of Shinar, Arioch king of Ellasar, Chedorlaomer king of Elam, and Tidal king of Goiim, these kings made war with Bera king of Sodom, Birsha king of Gomorrah, Shinab king of Admah, Shemeber king of Zeboiim, and the king of Bela (that is, Zoar). And all these joined forces in the Valley of Siddim (that is, the Salt Sea).” During the battle, Abraham’s nephew, Lot, is captured (Gen. 14:12), and Abraham sets out to rescue him Gen. 14:14-16. There are numerous elements of this battle in the biblical text which accurately reflect conditions in the patriarchal era, indicating its antiquity and not that it was invented over a millennium later, as those who hold to the documentary hypothesis suggest. First, names that are similar to the kings in this account have been found in other Mesopotamian texts from this period.12 Secondly, after the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur in the late third millennium BC, the area was not dominated by a single power; large and small city-states with ever-changing political alliances controlled localized areas.13 Thus, this passage accurately reflects the geopolitical situation of the patriarchal era. Price and Holden conclude: “The antiquity of this account within the larger context of the patriarchal narratives indicates that there is substantial reason to regard the whole as historically accurate.”14

6. Domesticated Camels

Scripture records that Abraham had a caravan of camels; his servant took ten of them when he went north to search for a wife for Isaac (Gen 24:10). Some suggest this is incorrect, an anachronistic detail, since Camels were not domesticated until the late second millennium BC or later, centuries after Abraham lived. For example, Donald Redford suggests that, “camels do not appear in the Near East as domesticated beasts of burden until the ninth century B.C.”15 Recent research, however has demonstrated that camels were actually domesticated before the time of Abraham. Ancient petroglyphs from Egypt and the Wadi Nasib depict humans leading camels who are tethered in the third and late second millennium BC.16 A late third or early second millennium BC bronze statue of a two-humped Bactrian camel with what appears to be a harness is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.17 In addition to artistic representations, numerous excavations throughout the Ancient Near East have unearthed remains of camels in domestic settings. Titus Kennedy concludes, “Bones, hairs, wall paintings, models, inscriptions, seals, documents, statues, and stelae from numerous archaeological sites all suggest the camel in use as a domestic animal in the ancient Near East as early as the 3rd millennium BC”18 In actual fact, domesticated camels gave their owners a great economic advantage, which is in keeping with the general portrayal of Abraham as a wealthy man.19

5. Asiatic Merchants in the Tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan

The book of Genesis describes the nomadic lifestyle of the patriarchs, and reports migration between Canaan and Egypt (Abraham in Gen. 12:10; Jacob and his sons in Gen. 42:5, 43:11, 46:5—7). When there was a famine in the land, Abraham and Sarah went down to Egypt. A painting in the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan, dating to ca. 1890 BC, portrays a group of 37 Asiatics from Shut (the area of Sinai and southern Canaan) traveling to Egypt to do trade.20 It is evidence of this migration pattern during the Middle Bronze Age and is a vivid depiction of what Abraham and his descendants may have looked like when they entered Egypt. Gary Byers notes, “Both the Biblical Patriarchs and the Beni Hasan Asiatics traveled from the same region (Syro-Palestine) to the same region (Egypt) during the same period (twentieth-nineteenth centuries BC). While no one proposes these are the Israelites, it is the right people, the right places and the right time to offer greater insights into the world of Biblical characters.”21

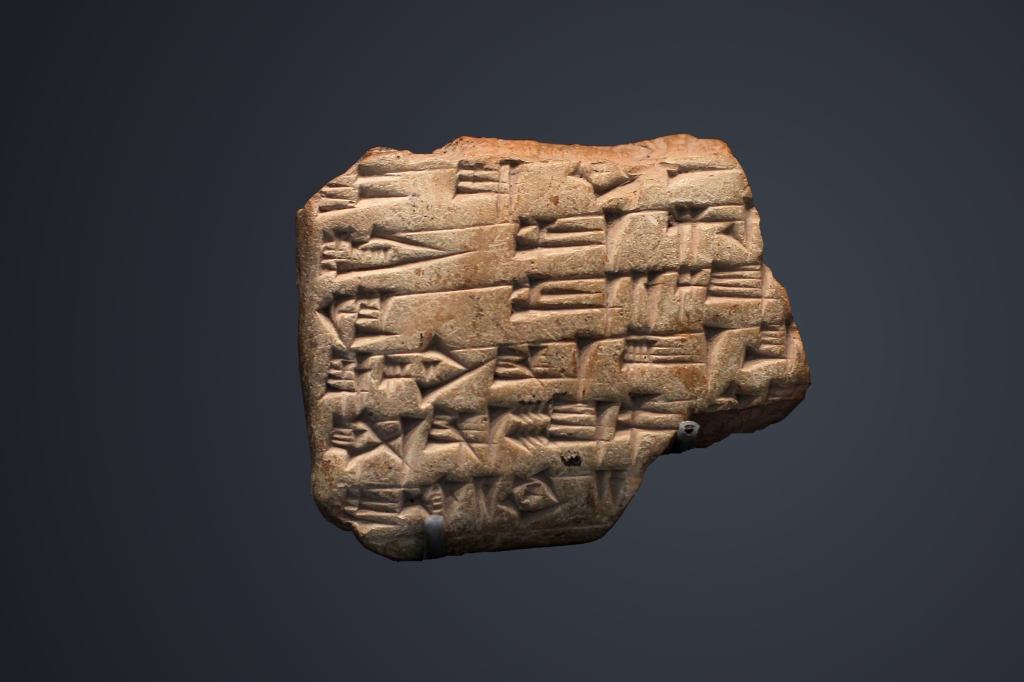

4. Mari Tablets

Mari was a thriving city for over a millennium (ca. 2800-1760 BC) and served as the capital of the Amorites from ca. 2000-1760 BC. Excavations, which began in 1933, have unearthed over 15000 clay cuneiform tablets from the city’s final years which provide a fascinating glimpse into the social, economic, and legal practices from that period, as well as examples of letters, treaties and literary works. The Mari Archive is an important archaeological discovery that helps us understand Amorite history and the broader culture in which Old Testament events occurred. While dating to a period after Abraham, they reflect some of the longstanding cultural traditions from the Patriarchal era. For example, the Mari texts reveal that, if a concubine bore the first son, his birthright could be withdrawn if the primary wife subsequently bore a son.22 Several places related to Abraham are also mentioned in Mari texts: a city named Nahur is mentioned, which may have been named after Abraham’s grandfather Nahor (Gen. 11:22-25), as well as the city of Haran (Gen. 11:31).23

3. Tomb of the Patriarchs at Hebron

When Abraham’s wife, Sarah, died, he purchased the burial cave and field of Machpelah from Ephron the Hittite (Gen. 23:16-18). Scripture records that Sarah, Abraham (Gen. 25:9-10), Isaac (Gen. 35:27-29), Rebekah (Gen. 49:31), Leah (Gen. 49:31), and Jacob (Gen. 50:13) were all buried in this cave. Given its importance, the Israelites remembered its location throughout the ages, and a monumental structure was built over the site by Herod the Great.24 Today, six medieval cenotaphs commemorating the burials of the patriarchs and matriarchs are inside the Tomb of the Patriarchs at Hebron. While the current political situation precludes proper excavation, several clandestine trips to the hallway and caves below the structure have been documented.25 Recently, four pottery vessels, which were taken from the caves during a clandestine incursion in 1981, were dated to the Iron Age, suggesting that the Cave of Machpelah was venerated by pilgrims during the First-Temple-era.26

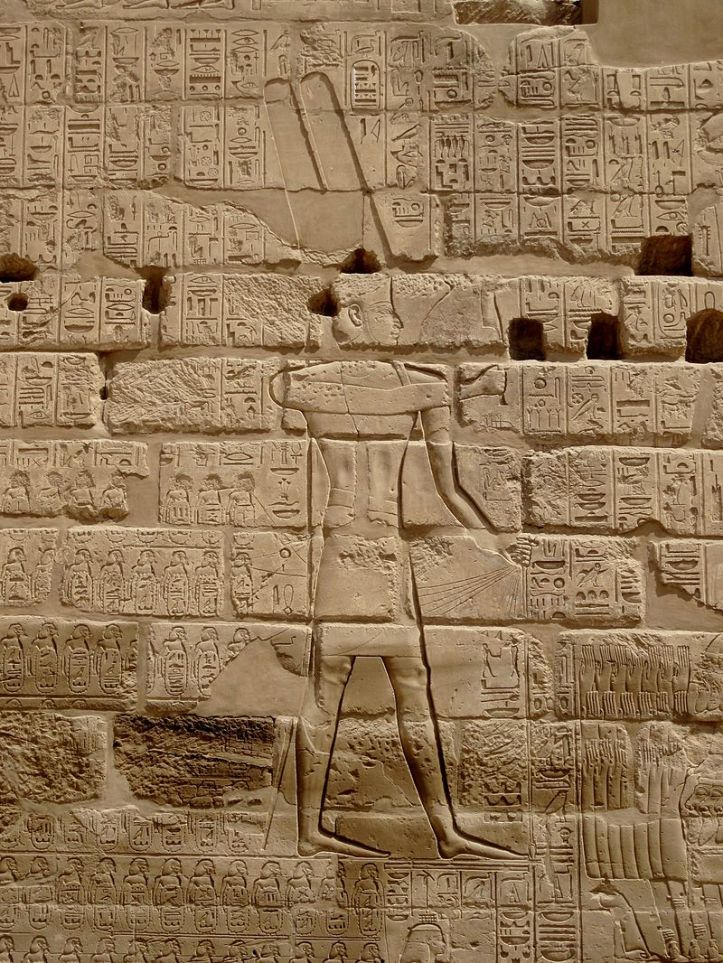

2. The “Enclosure of Abram” on Shoshenq I’s Topographical List at Karnak

The Egyptian Pharaoh Shishak (Shoshenq I), invaded the lands of Judah and Israel in 926 BC. When he returned to Egypt, he had a record of his victories inscribed on a wall of the Great Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak. He boasts of having conquered over 150 places, each “name ring” depicted as a bound prisoner with a cartouche beneath it on which a toponym is listed in Egyptian hieroglyphics. One of the ovals, located just below and to the left of Shishak’s right foot in the relief, reads, “the Fort/Enclosure of Abram.”27 This place was located in the Negev, a region that Abraham frequented (Gen. 12:1, 13:1, 20:1), which would fit well with a place being named after him.28 This is the only ancient, extra-biblical reference to Abraham.

1. Mt Moriah/Temple Mount

One of the most defining moments in Abraham’s life was when the Lord called him to sacrifice his only Son Isaac. In Gen. 22:2 we that God said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.” The region of Moriah is now covered by the modern-day city of Jerusalem, and Mt. Moriah itself is the Temple Mount, the place David built an altar to stop a plague, and where Solomon later built the temple in Jerusalem (2 Chr. 3:1). Joel Kramer helpfully notes that neither Abraham, nor David chose the location for their altars; the Lord directed them (Gen. 22:2 & 2 Sam. 24:18-19,24).29 Today, all that is visible of Mt. Moriah is the rock outcropping within the Islamic shrine known as the Dome of the Rock. Leen Ritmeyer has observed the remains of a foundation trench on this rock, which would have served as the foundation for the southern wall of the Temple. He has also calculated a 20-cubit square flat space on this rock, corresponding to the measurements of the Holy of Holies in Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 6:20), and noted a rectangular indentation in the rock, in the middle of the square, which is likely where the ark of the covenant stood.30 Mt. Moriah is the place God provided for Abraham a ram in place of Isaac, where God’s presence filled the First temple during the days of Solomon (2 Chr. 7:1), and where the curtain of the Second Temple was torn when Jesus died (Mk 15:37-39), signifying that his sacrifice of atonement was sufficient and the Holy of Holies is now open for all people – both Jew and Gentile.

Conclusion

Despite the fragmentary archaeological record during the Patriarchal era, numerous finds demonstrate that the story of Abraham accurately records cultural elements and places from that time period. This affirms the antiquity of the narratives of Genesis, and contradicts claims that the story of Abraham was the fabrication of a group of priests living in Babylonian exile (or later) who created him to invent a glorious history for their people. Rather, Abraham was a real man who lived at a real time in history. His faith in God was credited to him as righteousness such that he became the father of all who believe (Rom. 4:3-11).

Cover Photo: The statue of Abraham by Gian Maria Morlaiter (1754) at the Gesuati Church (Our Lady of the Rosary) in Venice. Photo: Dick Stracke/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

Endnotes:

1 Andrew E. Steinmann, From Abraham To Paul: A Biblical Chronology. (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2011), 68.

2 Steven Collins and Joseph M. Holden, Eds., The Harvest Handbook of Bible Lands. (Eugene: Harvest House Publishers, 2019), 34.

3 See “Chronology and the Patriarchal Lifespans” (p. 54-55) in The Harvest Handbook of Bible Lands

4 For a discussion of Tall el-Hammam and its identification as the city of Sodom, see Dr. Steve Collins’ explanation in “Is Tall el-Hammam really biblical Sodom? – Troweling Down Episode 1” here: https://youtu.be/fliRwnQiql4 and Dr. Bryant Wood’s explanation here: https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/patriarchal-era/3217-locating-sodom-a-critique-of-the-northern-proposal

5 Mark Wilson, Biblical Turkey: A Guide to the Jewish and Christian Sites of Asia Minor. (İstanbul: Ege Yayinlari, 2020), 42.

6 It’s interesting to note that Cyrus Gordon, an American Ancient Near Eastern scholar, who excavated with Leonard Wooley at the Sumerian Ur, never accepted Wooley’s identification of the southern site as Abraham’s “Ur of the Chaldees.;” he believed the Abraham’s Ur was located in the north.

7 Tony W. Cartledge, “Have We Erred on Ur?” Good Faith Media. Jan. 6, 2020. https://goodfaithmedia.org/have-we-erred-on-ur/ (Accessed July 1, 2021).

8 Todd Bolen, “Haran.” https://www.bibleplaces.com/haran/ (Accessed July 2, 2021).

9 Mark Wilson, Biblical Turkey: A Guide to the Jewish and Christian Sites of Asia Minor. (İstanbul: Ege Yayinlari, 2020), 38.

10 “Mudbrick Gate,” Tel Dan Excavations. https://teldan.wordpress.com/mudbrick-gate/ (Accessed July 8, 2021).

11 Todd Bolen, “Dan.” Bible Places. https://www.bibleplaces.com/dan/ (Accessed July 8, 2021).

12 Randall Price and H. Wayne House, Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017), 80.

13 K. A. Kitchen, On The Reliability of the Old Testament. (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), 320.

14 Randall Price and H. Wayne House, Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017), 81.

15 Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 277.

16 Titus Kennedy, “The Date of Camel Domestication in the Ancient Near East.” Associates for Biblical Research. 17 February 2014. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/contemporary-issues/3832-the-date-of-camel-domestication-in-the-ancient-near-east (Accessed June 27, 2021).

17 “Bactrian Camel,” Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/324256 (Accessed June 27, 2021).

18 Titus Kennedy, “The Date of Camel Domestication in the Ancient Near East.” Associates for Biblical Research. 17 February 2014. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/contemporary-issues/3832-the-date-of-camel-domestication-in-the-ancient-near-east (Accessed June 27, 2021).

19 Stephen Caesar, “Patriarchal Wealth and Early Domestication of the Camel.” Associates for Biblical Research. 19 February 2009. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/patriarchal-era/3444-patriarchal-wealth-and-early-domestication-of-the-camel (Accessed June 27, 2021).

20 Randall Price and H. Wayne House, Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017), 74.

21 Gary Byers, “The Beni Hasan Asiatics and the Biblical Patriarchs.” Associates for Biblical Research. Sept. 9, 2009. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/patriarchal-era/3978-the-beni-hasan-asiatics-and-the-biblical-patriarchs (Accessed July 1, 2021).

22 “The Rights of the Firstborn,” NIV Archaeological Study Bible (ed. Walter C. Kaiser Jr and Duane Garrett; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005), 43.

23 Bryant G. Wood, “The Mari Archive.” Associates for Biblical Research. Feb. 6, 2006. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/topics/amazing-discoveries-in-biblical-archaeology/3470-great-discoveries-in-biblical-archaeology-the-mari-archive (Accessed July 1, 2021).

24 “The Cave of Machpelah,” NIV Archaeological Study Bible (ed. Walter C. Kaiser Jr and Duane Garrett; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005), 38.

25 “Inside the Caves of Machpela,” The Hebron Fund. Feb. 8, 2018. https://www.hebronfund.org/inside-the-caves-of-machpela/ (Accessed July 8, 2021).

26 Bryan Windle, “New Study Analyzes Pottery Taken from the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron.” Associates for Biblical Research. Sept. 22, 2020. https://biblearchaeology.org/current-events-list/4734-new-study-analyzes-pottery-taken-from-the-tomb-of-the-patriarchs-in-hebron (Accessed July 8, 2021).

27 Kenneth A. Kitchen, “Shishak’s Military Campaign in Israel Confirmed.” Jewish History. http://www.judaicaru.org/rembrandt_rus/jh.php-id=Egyptian&content=content-shishaks_military_campaign.htm (Accessed July 8, 2021).

28 Kenneth A. Kitchen, K. A. Kitchen, On The Reliability of the Old Testament. (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), 313-314.

29 Joel Kramer, Where God Came Down. (Brigham City: Expedition Bible, 2020), 29.

30 Leen Ritmeyer, The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006), 246.